Elín Hall is loud and clear

Rising Icelandic talent Elín Hall tells Sophie Leigh Walker how storytelling lies at the hearart of her craft as both singer and actress – but in very different ways.

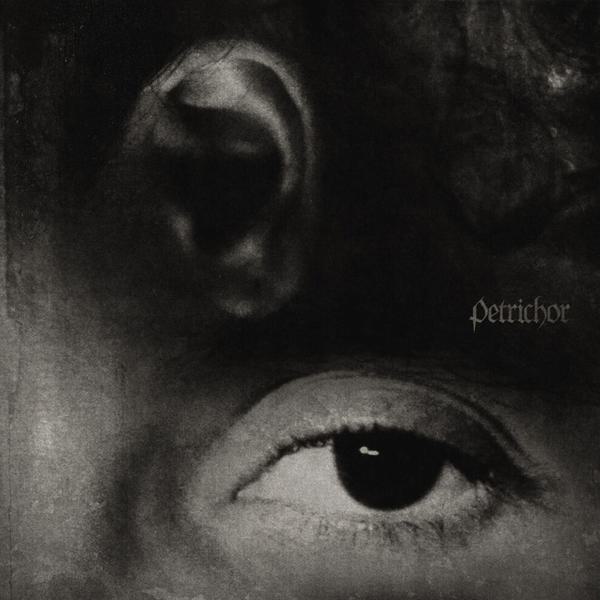

heyrist í mér? – Can You Hear Me? It begins as whispered doubt and grows into a scream cutting through the silence like a burning flare. Elín Hall’s album was christened with this question: a final demand to be heard and an act of surrender.

On the eve of its release, the Icelandic musician and actress was to perform the record for the first time at Fríkirkjan, a Lutheran church that dates back to 1903 and lies at the heart of downtown Reykjavík. Such a building might bring you closer to God, but with music, you’re almost brushing fingertips. Each November, the pews are full of these particular disciples; Iceland Airwaves, the country’s annual tastemaker festival, attracts music-lovers from around the world in droves. For those acquainted with the particular magic unique to Iceland’s artists, attendance becomes closer to pilgrimage. Despite the rapt audience sitting shoulder-to-shoulder, filling the venue’s hallowed rafters, Hall had decided that this was her swan song - destined for deaf ears.

“I wrote the album as a farewell to music,” she reflects, this time speaking to me with a year’s experience. The fact that heyrist í mér? would go on to win Album of the Year from English language newspaper The Reykjavík Grapevine; that she would perform on the Airwaves' main stage for its 25th anniversary; and that she would have written and recorded her third album, were more than unbeknownst to her but unimaginable: “I felt like I was screaming into the void. I was being perceived as an actress and not a musician – and a musician is what I was trying to be all along. I’d been working on it since I was sixteen, and I felt like the universe was telling me, ‘You’re going to make one more album, and that’s the end of it.’”

Though she may have once felt that her discipline as an actress was in conflict with her ambitions as a musician, it’s clear that the two are not only simpatico but lend each other qualities of depth and empathy inaccessible to those who don’t move between those worlds. Her latest film, When the Light Breaks, earned Hall her Cannes debut, where it was shortlisted in the Un Certain Regard category. She portrays a young woman grieving for her first love’s death; her performance communicates the shades of loss from a place beyond words - just as her music, in the unravelling of a guitar or in the gossamer of her voice, expresses something in a language of its own. “Something that was supposed to be a farewell kind of became the beginning of something,” she says.

At the core of heyrist í mér? there lies a tension. Sometimes, as with “Júpíter” her voice begins as intimate as a whisper, hot breath on your ear; the guitars are shy and there’s a distant sparkle of keys, as if they aren’t accompaniments but what remains of half-forgotten memories. But it changes, it grows – and then it snaps. A rusted guitar strum unleashes a hellfire of pummelling drums and Hall’s own screams, the ones that felt so silent. “It always felt like it was on the verge of becoming a rock album,” she shares. “I always wanted to stay on the verge of screaming. I think it reflects, emotionally, where I was at – going from this cute little singer-songwriter to having this dark, rock-driven cloud looming over everything.”

Hall started writing the record with her producer and then-partner, Reynir Snær Magnússon. He had worked on everything she had ever released, and she makes it clear that without his influence and belief in her music, she would not be the artist she is today. Their relationship ended midway through the project – but as creative partners, they forged ahead. “It felt like a child of divorce,” she laughs, “but it forced is to communicate because we were so passionate about the record. All of our friends thought we were just insane. I mean, it was kind of insane…”

Her lyrics are a confrontational and unsparing portrait of their fractured relationship. “It was very Fleetwood Mac, writing all these angry things about him, and then he would listen to it and his reaction would be like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s awesome. Let’s record that!’” she recalls. “It was very therapeutic for us both. By the end, it felt like we’d graduated from each other. It was cathartic, reaching the end of the road for us. I hugely admire him as a musician, he’s an incredible artist; we were together for five years and he made all my music with me.

"I definitely don’t think I would be doing this at all if it weren’t for him believing in me and pushing me to do it, but I think we needed to finish this album as a final goodbye. I don’t know what he got out of it, because with me writing the lyrics it was more obvious, but I think him taking a part in closing the chapter ended up being a very healing thing.”

It would be producer (and Vaccines bassist) Árni Árnason who would bring the record to completion with flourishes of atmospheric storytelling. Hall’s vision would be that it would feel “like a haunted house” guided by a tormented narrator. “rauðir draumar” was written as an embodiment of her character in Erlingur Thoroddsen’s 2023 Icelandic thriller Kudli. “It was an almost accidental method acting experience,” she reflects. “I was shipped into the countryside of Iceland in December, and I was alone in a cottage in the middle of nowhere.”

She was the only actor to sleep there for the duration of filming. The dark was interminable, it bled out of the role and into her surroundings long after the cameras stopped rolling. Hall insists the cottage was haunted: there were strange sounds and footprints in the snow which couldn’t be accounted for. The bleak internal landscape of her character soon felt disturbingly close to her own.

After sharing her desire to write a song inspired by the film, Thoroddsen shared playlists with Hall drawn from the 70s and 80s when the story takes place. She listened to iconic female-led Icelandic rock bands of the era who she channelled into the song’s inky beginnings and punk-driven coda. Her character falls in love with someone who cannot be trusted, and the song exists in the confusion between head and heart. “I’m not really interested in the black-or-white perspective,” she says. “I’m intrigued about what it’s like when you hate and love someone at the same time.”

In a sense, she tells me, Elín Hall is another character she invented in order to express herself. To serve another person’s vision an actress was never going to be enough. “For me, as a storyteller - because storytelling is what ultimately drives me as an artist – I will always have this thirst for creating music and being a songwriter,” she explains. “I don’t think I would be happy as a session player or a performer. I always need to be behind the message in some way. People are either interpreters or creators, and that’s the only issue I have sometimes with acting: it sometimes leaves me feeling like I’m not in total control. I need the freedom.”

She began as a dancer and developed into an actress – but music remains the only constant in her life. “There’s something about it that I find to be the blueprint of expression,” Hall says. “It’s like the earliest art form, something about how rhythm affects the brain. Even animals enjoy music. It’s so ingrained in humanity. I definitely don’t dance anymore – I don’t think I could do a pirouette to save my life – but I honestly don’t think I could ever stop writing music. I could stop releasing it, but using songwriting as a means of coping and expressing myself is something I can’t run away from. Acting is my day job, but I’m constantly thinking about lyrics.”

It's an instinct that runs in the blood. Hall’s grandmother is a beloved children’s novelist and lyricist, who nurtured her nascent passion for storytelling. “She has always been my role model. She would tell me stories all day, and we’d go for walks together and she’d tell me Icelandic folk tales. I seemed to think, as a kid, ‘Oh my god, my grandmother knows so many stories! How can she remember them all?’ I loved hearing them over and over again. But as I grew up, I realised she was just making them up as she went. She taught me to see stories in everything. I’m like her, in a lot of ways… She’s 90, and yet she’s so bright and sharp – and that’s ultimately what I respect about her the most. She’s had a very hard life, but she just had this mindset of finding the silver lining in everything. She also sings ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ at least twice a day – and no, she isn’t even a Liverpool fan! My grandmother was the only person I had to look up to creatively, and gave me the confidence to express myself. I’m so proud of her as a writer.”

The opening track on the album, “he i m” – home – conjures a nightmare of Hall’s which takes hold slowly. Peeling graffiti, stinging nettles, a long-abandoned swing set squeaking in emptiness. A trail of blood leads to the attic. These were the images that haunted her sleep when her father was selling their childhood home. “I couldn’t sleep because I was having nightmares about it and memories from growing up, but they were distorted and strange and disgusting,” she recalls. “It was so uncomfortable, because I had a very happy childhood, and it felt like in writing the song I was ruining these memories.” It was only after she committed these vandalised remembrances to record that she realised where they had arisen from. “To me, it’s about having to let go of your childhood. Because it’s so brutal, growing up,” she reflects. “My parents divorced and everything just became real and rough so suddenly. It’s hard to look back on a beautiful childhood because I became such an emotional teenager. It’s strange how something so beautiful can be almost too painful to look at.”

Her lyrics are almost novelistic, a Swiss army knife of sharp metaphors tempered with incisive, unflinching truths. In Icelandic, they can be felt universally – but understood by few. Hall’s forthcoming music, which she unveiled for Airwaves at the Reykjavík Art Museum, marks a definitive turning point because, for the first time, she is writing in English. “It wasn’t a natural progression for me because I’ve been honing in on the craft of writing good Icelandic poetry. For many years, it was my only goal,” she shares. “I felt like I really needed to start from the beginning in English. I haven’t experienced a heartbreak in English – I have only experienced it in my own language. I couldn’t get it out of my head that my lyrics are never going to be true enough in English because I haven’t experienced life through that lens.

She started making the journey to London to write new music, and her experiences in that language broadened accordingly. Not only will Elín Hall be heard, but she will be heard on the scale the quality of her music demands. “I’ve started to appreciate that maybe language isn’t the most important thing. I put this wall up for myself between Icelandic and English, as if it’s a mountain I can’t cross,” she says. “But I think, essentially, it’s feelings and experiences that will resonate. As humans, we relate to things universally no matter our background, country or language. I figured my experiences aren’t so rare.”

Elín Hall performs at SXSW 2025 next March. Iceland Airwaves returns to Reykjavík from 6 - 8 November 2025. Icelandair are running package trips to the event – simply choose how many days you want to spend in the country, and they take care of the flight, festival pass, and optional hotel and airport transfer. Find out more about Airwaves at airwaves.is.

Get the Best Fit take on the week in music direct to your inbox every Friday

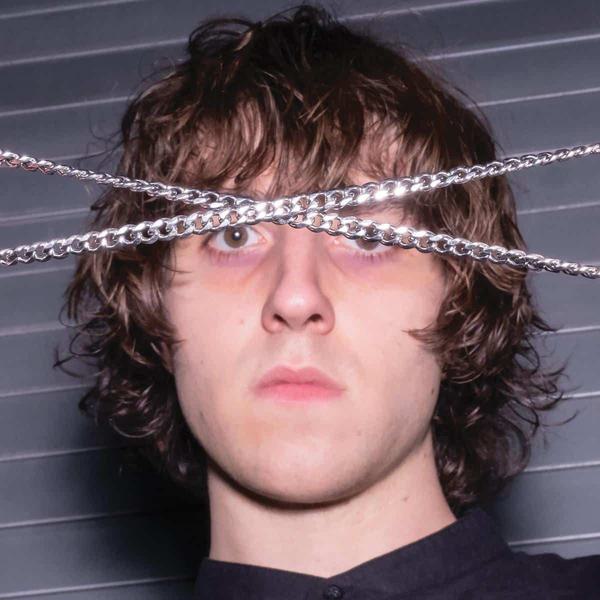

Cameron Winter

Heavy Metal

Sasha

Da Vinci Genius